Quick update: I missed last week and I’m 3-days late this week, trying to figure out that whole doing too many things, thing. Thank you for your patience.

And I apologize for disabling comments, that was by mistake. Comments are enabled on all posts and will continue to be in the future.

In the previous chapter, I took a big ethical dump on virtue-signaling organizations that aim to profit from their own do-gooding. I relieved myself because I see attempts to capitalize on would-be altruism as a form of greed so good it would make Gordon Gecco blush.

You, the reader, may have come away with the impression that I have no place in my shriveled heart for social progress helmed by corporate Earth. And that perhaps I feel no corporation can meet my lofty righteous requirements and benefit from their acts in the marketplace. Cue the exception drumroll.

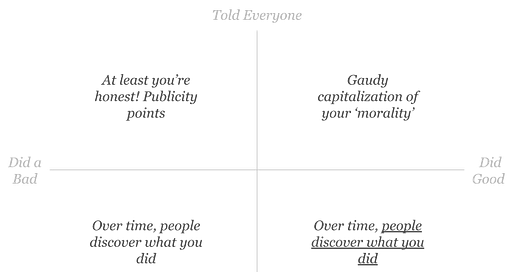

When I last left you, I suggested you run your company the way you believed was right, and to avoid marketing your beliefs. Organizations which follow that path find themselves at the bottom-right of this two-axis chart:

The awful things a company does eventually come to light: the Sacklers hustled Opiods1, DuPont knowingly released PFOAs into the environment2, and PG&E was directly responsible for causing cancer in Erin Brokovich’s community.3

If we eventually learn about the terrible things a company does, then we must also learn of some good things companies do. That’s the bottom-right quadrant, and I call it the slow-burn morality play.

The Slow-Burn Morality Play

Costco does not advertise nor mention in its marketing materials that they happen to offer an average starting pay of $14.4

I pulled up that metric because a decade ago my father commended Costco for paying high wages relative to its category and for being a great place to work – something he heard through the grapevine. And as best as I recall, I never heard that from Costco or read it in any consumer-targeted marketing campaigns, and I’ve been a member for over two years.

Yet in 2021, there’s no better time for Costco to capitalize on these facts. Democrats regained power this year, and like clockwork, the progressive wing of the party once again rang the federal minimum wage gong.

Costco is positioned to capitalize on the trending social movement by coming out in favor of a minimum wage increase. They can show off internal statistics and confess that they happen to be on target to increase all starting wages above $15 ahead of their competition and the federal government itself – wow, such woke. But they will never do that.

Costco won’t do this because they’re run by people with a brain cell surplus.

The moment Costco claims moral superiority, every Twitter journalist, and some real journalists will unsheathe their digital microscopes in search for proof of Costco’s malfeasance. And where there’s digging, there’s dirt.

All it takes is one former employee to spill a one-sided story to BuzzFeed and it’s one step forward, two steps back into a steaming hot pile of bad publicity.

Meanwhile, Costco customers, partners, and employees in disagreement with federal minimum wage increases suddenly find themselves in ideological conflict with a brand they respect and depend on. Most will remain with Costco, but some will look elsewhere for more agreeable partners.

But Stanley, you think to yourself, what about all the customers, partners, and employees Costco might gain by attracting like-minded individuals and organizations? Excellent point, reader, here’s exactly what I think about that.

Beliefs Are Not Assets

We cannot monetize a belief. Most companies exclude beliefs from their go-to-market strategies because value, and not belief, is the primary variable in market relationships: what customers get and what they pay for it.

Remember, it doesn’t matter how much your customers agree with you if they can go on happily without your services in the first place. A belief is not value, it’s merely an opinion, and any of your competitors can hold it.

You can’t patent a belief, package it, or put it on your balance sheet. Which is to say, in many situations, the people we attract to us through shared beliefs prove unsatisfactory partners because it was belief which attracted them, not equitable value.

I’ve watched my wife go through this with salmon shares, organic farms, and other businesses with virtue-forward messaging. Ultimately, despite aligning with their virtues, we fail to sustain commitments due to a lack of value.

Exceptions must exist, but it’s my opinion that belief-driven partners are fair-weather fans – I’d rather have customers who value my services than those who value my politics.

In Costco’s case, they merely do what they think is right, meanwhile, employees and in-the-know customers do the marketing for them. As you know, word of mouth is the most powerful form of marketing.5 And word of mouth is the best way to learn that a person or an organization does amazing things when you’re not looking.

Humble Virtue

Humility in tandem with virtue attracts us to both people and brands. On average, I believe we mistrust what others tell us about themselves. If you tell me you’re an award-winning DJ, I’ll make you lay down some tracks to prove it.

But when someone I trust tells me you’re an award-winning DJ, the motive to impress disappears, as does my guard – I trust the information as presented.

My father had no reason to tell me Costco paid well or offered a great working environment, I had gainful employment at the time. Whether his statement was true, I was likely to believe it and it left an indelible impression of a brand I would ultimately partner with, as customer.

Think about the good that your organization does and how traditional marketing effects may play an outsized, but unquantifiable role in your success.

Just as in our personal lives, we cannot measure everything great that comes to us as a quantified return on our good deeds, we just do the right thing and have faith that the laws of the universe reward us in kind. That’s as true for Dan Johnson as it is for Johnson & Johnson.

In case you missed it, I’m writing a book. One newsletter at a time, I’m delivering a chunk of a book tentatively titled, The Marketing Bible: Sell Your Products, Not Your Soul, a guide to ethical marketing.

Follow along as I share my beliefs in what will become a fully-packaged book.

Readers who contribute comments, suggestions, and critiques throughout this process are eligible for free copies of the finished work circa Q4 ‘21/Q1 ‘22.

Previous: Thou Shalt Not… Signal Thy Virtue

“Purdue Pharma Is Dissolved and Sacklers Pay $4.5 Billion to Settle Opioid Claims,” The New York Times, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/01/health/purdue-sacklers-opioids-settlement.html.

“The Lawyer Who Became DuPont’s Worst Nightmare (Published 2016),” The New York Times, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/10/magazine/the-lawyer-who-became-duponts-worst-nightmare.html.

SKILLMD, “Erin Brockovich and Hexavalent Chromium,” SKILLMD (SKILLMD, 2014), https://www.skillmd.com/erin-brockovich-and-hexavalent-chromium/.

“Costco,” ZipRecruiter (ZipRecruiter, 2021), https://www.ziprecruiter.com/Salaries/Costco-Salary-per-Hour.

“Is Word of Mouth Better than Advertising? | Jonah Berger,” Jonah Berger, 2013, https://jonahberger.com/is-word-of-mouth-better-than-advertising/.